By Jim Spencer

Well-prepared, properly stretched and dried fur pelts are usually worth more than green fur, but a poorly handled pelt is worth far less because there aren’t any do-overs. Here’s a step-by-step guide for getting it right.

Set up a work space

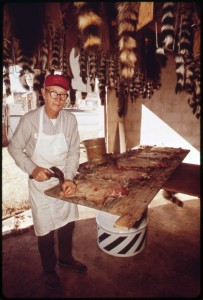

Fur handling areas can be elaborate or simple, small or large. Part of an attic or basement can work, but fur handling is messy and smelly. A garage, tool shed, shop building or other outbuilding might be better.

You need room for skinning and hanging wet animals so they can dry. Many trappers use commercially made or homemade skinning gambrels, and I have one for ’coons, otters and coyotes. For other animals, I prefer a loop of soft rope eye-bolted to a sturdy rafter. The rope is half-hitched around an animal’s hind foot to hold it at shoulder level. Elsewhere around my shed are a dozen or so lengths of wire attached to other eye bolts, for hanging wet animals before skinning. For skinning beavers, you’ll need a sturdy flat table or bench about waist high. My fleshing beam is in a corner, with a plastic bucket to hold the fat, flesh and other scrapings.

You also need a place to hang stretched pelts while they’re drying and afterward. If your fur handling area has exposed rafters, it’s a simple matter to drive a series of nails or cup hooks along the rafters. If the ceiling is enclosed, drive the nails or hooks into a long 2-by-2, and then attach it to the ceiling with screws or bolts. Put up as many hangers as you have space for. You’ll be surprised how many you’ll need.

Proper field care

The first step in good fur handling begins in the field. Beavers and otters don’t require much in-the-field care, except to avoid stacking them on top of each other so they can cool and air-dry as you finish running your line. These short-haired furs dry quickly. Otters are susceptible to singeing, though, so keep them away from freezing metal, and keep them from rubbing against equipment or other furbearers during transportation.

If wet, mink and muskrats require more attention. Rinse any muddy animals at the catch site, and then squeegee excess water out of the pelt with the edge of your hand. Hold a wet mink by the head and pop it several times, and then grab it by both hind feet and repeat. (Don’t pop wet muskrats. It breaks their backs and makes skinning more difficult.)

Next, roll the still-damp mink or muskrat into a double layer of newspaper, and lay it in the back of your vehicle. As with beavers and otters, try to avoid piling warm mink and ’rats. By the time you start skinning, all but the most waterlogged specimens will be dry and fluffy.

Wet possums and ’coons are tougher. If one of these is muddy, wash it thoroughly, even if you end up with a wetter animal. The mud has to come out eventually, and it’s easier to remove when it’s wet.

’Coons and possums are larger than mink, so they’re harder to pop, but you can get a lot of water out of the fur this way. Using your hand to squeegee the animal also helps. Then, if possible, lay the animals so they don’t touch in your vehicle, and let them air-dry as you finish your run.

For predators such as fox, coyotes and bobcats — and dry ’coons and possums as well, incidentally — the most important things are to avoid getting the pelt bloody and to allow the furbearer to cool quickly after being killed. If you shoot these furbearers, try to lift the animal by a hind foot while it bleeds out. When you put the animal in your truck, wrap its head in several layers of newspaper or old rags to absorb the blood and keep it from soaking into the fur.

Skinning

Sharp knives of the proper size and shape are essential for efficient skinning, but other tools are important, too. A butcher’s sharpening steel is useful, as are poultry shears, shop rags or towels, a plastic or rubber skinning apron, and latex or nitrile disposable gloves. The gloves not only keep your hands cleaner, they also help protect from disease. Never skin furbearers without gloves.

Here’s my case-skinning method: Hang the animal from one hind foot at eye level. Cut around all four feet at the ankles and wrists. With muskrats and nutria, ring the tail at this time, too, at the hairline.

Grasp the loose hind foot, pull it until the skin between hind legs is taut, and cut along the back of the legs from one ankle to the other. With most furbearers, the connecting straight-across cut will pass just behind the vent, but with raccoons, the proper cutting line is farther around on the belly, about halfway between the vent and the penis opening on a male raccoon.

Cut around the sides of the vent to the tail base, and split the skin about a third of the way on the underside of the tail. Using your knife to get things started, work the skin away from the tailbone and off the back legs. Pull the tailbone the rest of the way out of the tail skin.

Continue to work the hide off the rear legs and then pull the pelt down over the body. As the front legs come into view, pull them free from the pelt. Continue pulling the pelt down over the neck (some careful knife work might be necessary here on canines and cats) until the ear butts show. Carefully cut through the cartilage at the base of each ear. Pull the pelt a little more, and the edges of the eyes will become visible. Cut the eye holes loose, being careful not to make them larger than necessary. Give the pelt another tug, and it will come loose to the corners of the mouth. Make another careful cut on each side to free the lips, cut off the bottom lip, and skin the rest of the head all the way to the tip of the nose.

Beavers are skinned “open”. Lay it belly up on a flat, sturdy work surface. Ring the feet and tail at the hairline, or use heavy shears, loppers or a hatchet to cut off feet and tail. Make a cut along the midline of the belly from chin to tail, cutting carefully around each side of the vent. Next, switch to a curve-bladed knife, and peel the pelt back from both sides of the cut, working around to the beaver’s back. Continue cutting and pulling the pelt until the tail section is free, and work the legs free of the pelt as you come to them. When the pelt is free from everything but the beaver’s neck and head, roll the carcass onto its belly, and let the pelt hang down over the head, using its weight to hold the pelt tight as you finish the job. Follow the procedure for the ears, eyes and lips outlined above, and skin all the way down to the tip of the nose.

Fleshing

Mink and muskrats are easy.

Mink first.

Pull the pelt over the board (my mink and muskrat fleshing beam has the same dimensions as a mink board but is thicker so it won’t flex) so that the belly and back are on the edges of the board, and the sides of the animal are on the board’s wide surfaces. Beginning around the ears and lips, carefully scrape the loose fat and flesh away from the hide, using the dull side of a double-handled fleshing knife and pushing the flesh down the hide. Work the fat down toward the front legs, but stop just before you reach them. Bring the other side of the pelt to the top of the board, and repeat the process.

When you reach the front leg, move the pelt so the leg is over the rounded end of the board and the belly is mostly on your side of the board. Begin scraping where you see the little glob of fat under the front leg, and continue down the belly side of the pelt, scraping off the fat usually on the lower belly of mink and muskrats. Position the other front leg on the point of the board, and scrape it the same way, getting the other side of the belly in the process. Leave the red saddle of flesh on the back of the mink pelt; most buyers prefer it that way. After you’ve learned how, this process won’t take 90 seconds.

Muskrats are fleshed on the same mink stretcher-shaped board, and they’re even easier. Put the pelt on the stretcher with the back of the pelt facing you, and make a couple of light swipes down the whole pelt to remove any loose flesh or fat. Stop right there; the back is now clean enough. Turn the board over, and remove the loose flesh on the belly side, being sure to get the stuff in the “armpit” area. Don’t scrape too close; just getting the gobs of stuff off is good enough.

For larger, long-haired pelts — ’cats, coyotes, foxes, ’coons and ’possums — I use a larger, longer fleshing beam, but stay with the 12-inch, two-handled fleshing knife.

The drill is similar to fleshing mink and muskrats, except the scale is larger. Possums are usually very fat, but again, you don’t want to scrape them too closely. Do so, and you run the risk of tearing the skin or damaging the guard hairs. Just take off the big gobs of fat and meat, working the pelt around the beam so you can reach every part of it.

’Coons are tougher and require more elbow grease. The process is the same, though: Start around the ears and lips on each side, work down to the neck and shoulder area, and then position the front leg holes over the end of the beam, one at a time. Then remove the fat and flesh. Scrape ’coons as clean as you can get them. Pay special attention to the gristly stuff on the neck of a coon pelt, high between the shoulders. This tough area often requires heavy labor and careful shaving with the sharp side of your two-handled fleshing knife.

Bobcats, foxes and coyotes usually don’t need much scraping, but occasionally you’ll find a little fat under the armpits or, more commonly, on the lower belly — especially on ’cats. A few light passes with the two-handled knife are usually enough to clean this up. Scrape ’cats and foxes lightly and carefully, though, because their skin is thin and papery and tears easily.

Fleshing beavers and otters involves little finesse but a lot of hard work. Pay special attention to the tail and lower belly of an otter. The fat and gristle here is tough as leather, and the belly will easily taint if it’s not thoroughly fleshed. Otter pelts are prone to singe when being fleshed, so be sure the fur is slightly damp when you pull it onto the fleshing beam. If it’s already dry, dampen it with a few sprinkles of water.

Stretching

This is the easiest part. Wire and wood stretchers will work, but mink, otters, weasels, marten, fisher and ’coon usually look better and sell higher when stretched on wood.

When using wire, pull the pelt on the stretcher fur side in, centering the belly and back on opposite sides. Starting with the belly side, fasten the back legs using the metal fur hook on the stretcher, and pull it down until the pelt is smooth and firm. Turn the stretcher over, and fasten the back of the pelt at the base of the tail, pulling the hook until this side is firm as well. For ’coons and possums, turn the stretcher back to the belly side, and cut away the loose pouch of skin on the lower belly.

After about 24 hours, remove ’cat, coyote and red fox pelts, turn them fur side out, and put them back on the stretchers to finish drying. Leave other species (including gray fox) skin side out. Gray fox can be turned if you prefer; buyers will take them either way.

At least two sizes of boards are needed for mink, for males and females. Center the pelt on the board as described above. First, put a temporary pin in the center of the tail at its base, where it joins the body. Then pull the back legs around to the back side of the board, and tack them close to the base of the tail. Working from one side of the tail to the other, tack the tail out flat and as wide as possible, putting the pins a half-inch to an inch apart. Finish the tacking process by pulling the edge of the skin at the back of the legs toward the tail and pinning it there. Put a wooden wedge between the board and the belly of the pelt, and you’re done. The process is the same for ’coons and otters, except, of course, the board is bigger, and a ’coon’s tail is not tacked down.

Beavers can be stretched on hoops or plywood. If you use hoops, you’ll need a spool of nylon string and a bagging needle, or a lot of hog rings and a pair of pliers. First, lay the pelt on the board, and use a sharp knife to cut off an inch or two of the fatty “face” of the pelt, cutting just in front of the eyes. If you’re lacing, start at the front, lacing through the edge of the pelt and around the hoop at 1- to 2-inch intervals, working all the way around the hoop. To keep from having to pull so much string through the holes, it’s helpful to cut the string and tie it off about a quarter of the way around the circle, and then start fresh with a new length of string. When the pelt is fully laced into the hoop, loosen the sliding set-screw, and enlarge the size of the hoop enough to tighten the pelt inside the hoop.

If you use hog rings, put one ring at north-south-east-west on the pelt, and then split the difference again between the four rings, and attach four more rings. Then adjust the hoop to hold the pelt not quite tight, and keep on taking up the slack by adding more hog rings until the pelt is held onto the hoop all the way around, with rings at 1- to 2-inch intervals. Adjust the set-screw if necessary.

If you’re tacking the pelt to a board, lay the pelt flesh side up on the board, and drive a 2-inch finishing nail at the nose and the center of the tail. Then put two more nails at the sides, so the four are in the shape of a cross. Now, start splitting the distance between nails, putting four more in so there are eight nails spaced equally around the sides of the pelt. Keep on splitting the distance with more nails — 16 nails, and then 32 and so on — until the nails are one to two inches apart. Use a screwdriver to raise the pelt on the nails around the edges for air circulation.

Whether you use boards or hoops, the stretched green pelt should be pulled just tight enough so all the wrinkles are removed and the skin doesn’t sag when hung up to dry. If the green hide feels like a drumhead, it’s too tight.

Is It Worth the Bother?

Properly stretched and dried furs are almost always worth more than green stuff. Also, putting up fur gives a trapper more selling options.

The down side, of course, is that it’s more work. Converting a pelt from “the round” to a well-handled fleshed and dried product requires considerable time and energy. Whether it’s worth it is up to the individual trapper.

But when I walk into my fur shed and look at those rows of well-handled pelts, it gives me a feeling like no other. Forgotten are the long hours in the fur shed, and I catch myself just standing there among those pelts and looking at them.

Yes, it’s worth the bother.

Jim Spencer is the executive editor of Trapper & Predator Caller. For information on Spencer’s trapping and turkey hunting products, visit his website at www.treblehookunlimited.com.