How to utilize the lay of the land to elevate your fur harvesting success.

Text by Cary Rideout

Photography by Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

How often do you run into this situation? A section of country is too tough to set, the ground is all wrong and you just can’t figure it out! Well, is it really that difficult or are you looking at the problems instead of the obvious solutions? Long before you break those first springs open, it might be better to work on your geography skills.

Cartography 101

Electronic options, GPS maps and cell phone apps like OnX Hunt are now readily available at everyone’s fingertips. A map, however, is about like any tool and only as good as the person using it. Maps offering trapping information fall into two basic types: the county or local area map, and the topographic map. Always be sure they are current since terrain can change with a new road or logging operation. Local, state and federal maps provide good coverage of roads or fire lanes and trace watersheds in great detail. Forest Ranger and farm extension offices can also provide good maps for a fee.

The key or legend will clearly explain all of the various symbols on a map, and needs to be studied carefully to use correctly. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

A good topographic map clearly explains the degree of slope and the height of any sections of higher ground. These appear to be concentric irregular circles, each numbered so many feet above sea level that will slowly get smaller until the summit is reached. A long series of these denotes a line of hills and any divides up through will also be noted in a lower height number. On some topographic maps, terrain features may be shaded in various colors denoting elevation changes. Streams and lakes can also be carefully examined on a topographic map. With modern connectivity you are able to access a wealth of maps online and on your phone from various sources like OnX Hunt, and many trappers still also prefer the paper type since the battery on those never seems to fail.

Map reading, whether on paper or on an electronic screen, has its own language and you will need to find the legend or key that is usually located along the edge. This key or legend will clearly explain all of the various symbols on a map, and needs to studied carefully to use each map correctly. Brooks, rivers or lakes, swampy ground and any dams will be represented by a symbol. Various colors of lines indicate roads, ATV or snowmobile trails, power lines and sometimes even decommissioned right of ways. More importantly, good maps should have colors to differentiate forest or wooded areas from farmland and open areas crucial for trapping. Topographic maps do have more physical detail, but many folks are fine with standard county maps. Be very certain you understand the bar scale of so many inches equaling so many miles. You don’t want to misunderstand this — believe me.

Mountains High, Valleys Low

While most furbearers tend to avoid mountaineering, there are certain less-than-level terrain types they do wander through. No one wants to be nose down climbing, but a gradual slope seems to be almost a beacon. Fishers are legendary for liking a good climb, almost relishing uphill jaunts. While certainly predictable about returning to the home area, give them a stretch of dry, late-autumn weather, the whiff of new country over the next ridge, and they can take off for days wandering around. I’ve tracked many a long-walker over miles of broken hills, and learned that a critter that has a desire to travel doesn’t just climb pointlessly — instead preferring a route with good footing. Wild wanderers seem to instinctively recognize the angle of ascent that will get them up and over with the least amount of effort. Unlike a spooked whitetail, a furbearer is at its leisure and works around any obstacles, always going up at an angle. This is another good example of terrain that needs prep work and a few hours of tracing the contour lines can save days of unnecessary footwork.

Many times old farm fields will grow up in spruce right up against the older hardwoods to form a very clear delineation. These tree line differences, with their heavy overstory, provide comfortable passage for any wild traveler. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

After taking all of this into consideration, why not work smarter and set to the terrain conditions? For some reason we trappers are wired to always go farther when setting in hill situations, often climbing far more than necessary. Instead, after you’ve identified the uphill route, why not make a set near the bottom and another a couple hundred yards above? Don’t go any higher than that, and when the travelers return you’ll get ‘em.

Smaller hills are equally worth examining when considering a piece of new country for fur potential. If you are doing a thorough map search, trace the lower foothills and see if they block a watercourse. Headwaters often begin at the foot of a low section of hills. A stretch of hills can separate fur trapping areas with a swamp or lake on one side and maybe cropland on the other. With this kind of terrain a trapper can be sure of fur traveling back and forth between the two.

Trappers all know about the broad sweeping valleys that cover hundreds of miles, but what about the other kinds of low spots? Many smaller valleys can be gold mines, particularly if they are super narrow and focus travel in the right direction. Sometimes the obvious is only so if you rethink your idea of what makes a valley.

What about the shallow valleys running through farm fields or rough drainage ditches? Some are really low and can’t be seen from a distance, but fur can be right by the truck window if you just look a little closer. Farm country abounds with edges in low valleys that can run for miles, and can be fur hotspots. These places allow travel under the radar and out of sight — perfect for a snare line — as they are usually filled with brush for winding up a snare set. Some will get wet as the autumn rains come, but many target species are not as averse to damp feet as you might think, and once the ice comes they seem drawn to travel these frosty features.

Another positive point about a smaller valley is the surprising amount of prey they can hold. Birds, rodents and all sorts of small game like the access to farm grub and the cover that an overgrown small valley or abandoned ditch provides. After some effort with the maps you’ll soon understand the terrain needed to find such locations.

Irregularities & Oddities

Big terrain like mountains and broad sweeping valleys certainly grab a trapper’s attention, but what about the countless oddities and irregularities that good fur country abounds in? Every critter that travels seems to notice the location of rocks and stumps, that for some reason we trappers choose to overlook. Many of the best fox trappers I have questioned all spoke well about the great oddball stuff they once relied on to fill fur sacks.

A good, large boulder or stubborn ledge projecting well above the ground level is certainly a fox favorite. Reds seem to like the height these offer to stretch out, while keeping a wary eye for trouble or prey. Look over each one that you can and even if they don’t show any recent sign, don’t be fooled because the fur knows where they are. A couple squirts of fox urine right where you intend to lay steel will be pay off later. What? You don’t carry a squirter of pure fox pee when you wander? Believe me — it will get half the job done when it comes to any irregularities.

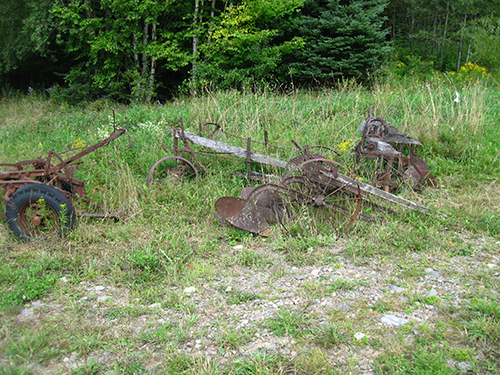

Not all terrain is natural. Old farm machinery or the rusty junk we humans leave all over the landscape are readymade resting places and food counters to furbearers. Abandoned autos or farm trucks are always popular with raccoons as hangouts, too, so scout carefully for droppings or hair. These ‘coon condos can be perfect for a few bucket sets. Skunks and opossums also use them. As winter storms move in they become stopovers as various bandits prowl about putting on body weight. Check out any and all buildings, no matter the condition — even the fallen-flat ones.

Old farm machinery or the rusty junk we humans leave all over the landscape are readymade resting places and food counters to furbearers. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

One of the most obvious oddity that stands out is the lone tree in an empty landscape. You prairie prowlers are likely familiar with them. One along a trickle of a watercourse is about perfect, and add good-eating crop fields and you are in the money for fur. Another oddity is the random hay or straw bale or the solitary runaway off to the edge of a field that are never picked up. These are rodent cities and provide both a visual and food draw.

Clumps of rank grass and short bushes all break the terrain and can be used as irregularities. Look for objects that catch the eye and stand out as not belonging. One of the most common irregularities on my traplines are the countless rock piles that populate forests and fields. Big or small, these hold tasty rodents that attract hungry autumn fur, and are good spots to add a few long-tailed weasels to the count. Updated aerial photos found online and on the OnX Hunt mapping system will assist you in locating those old rock piles in your neck of the woods.

Even after the snows come a few stubborn rocks keep poking up and can be used for snow sets. Old-time snow trappers used this terrain feature and it still works. Raccoons also like searching the stone heaps, as do skunks. Various fruit trees often grow nearby, especially around old abandoned homesteads, such as wild plums or apples, as do raspberries and rose hips. Foxes and others will show up for all of the bounty this kind of terrain provides.

Stumps or any storm-damaged old sections of tree trunks are also good trapping spots to investigate. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

Stumps or any storm-damaged old sections of tree trunks are also good trapping spots to investigate. A couple kinds of sets should be used at these locations, and remember to use lure/bait the target furbearers would find in this situation — so break out the mouse traps in July. A stump needs to be at least a foot tall or higher to stand out along a trail and it’s better if it’s a bit rotten, as well. The big roots might give you trouble so dig around early to find the soft spot to work with. Bobcats can never pass a stump without leaving a few sprinkles on it.

As the autumn weather moves in there is another seasonal terrain feature you ought to be mindful of. Random water pools appear and can be a way to get another pelt over the fur forms. The masked brethren seem to be unable to pass by water and not dip their paws, and the same goes for foxes. For some reason the shimmer of moonlight on any water will draw a red to wander over and at least get a sip. Old machinery tracks will quickly fill up with rain to become instant sloughs, and wooded country often has a few small ponds that appear as the trapping season approaches. Don’t be too quick to discount this kind of terrain. I’ve set along these mini water courses and caught fox and ‘coon often enough. Just be aware this is a time-sensitive set and frost will soon freeze it up.

Mounds of dirt and clumps of rank grass all break the terrain and can be used as irregularities. Look for objects that catch the eye and stand out as not belonging. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

Along The Green Line

The best forested trapping terrain must have food and travel corridors. Food sources like nut or berry bushes can be busy freeways of activity as ripe fruit comes down. Both predator and prey species will be in a frenzy to gorge themselves before it’s all gone. Now, of course, by trapping time the free lunch is long gone, but fur has a good memory and will return to a former bonanza hoping for a mouthful. Set around any and all wild food trees you encounter to take these return customers.

No section of wooded terrain is better suited to fur trapping than where coniferous and deciduous trees are clearly divided. These green lines of separation can offer fur prospects for a trapper willing to search them out. Here in the North Woods, forest can change abruptly from maples to balsam fir, but in other areas it might be mixed more than several hundred yards. Again, this is where aerial photos can really shine, and give a distinct advantage to your scouting and setting.

Many times old farm fields will grow up in spruce right up against the older hardwoods to form a very clear delineation. These tree line differences, with their heavy overstory, provide comfortable passage for any wild traveler. Another clear change of terrain is the alders or other brook-loving brush bordering the tall timber. Martens, fishers and other slim travelers all abound, as do the the top food sources of the woods — the hares or rabbits everything dines on. Those spotted bobcats the furriers love prowl this kind of terrain, as well. Use a good, solid enclosure with a couple wings of snares on the outside for a variety of targets. A smart trapper in this type of country will also look for game trails running right along the line of difference and hang a few snares there.

No discussion on terrain would be complete without mention of the deciduous desires of beavers. A good many profitable beaver lines, and yes at one time beaver was a guaranteed profit, were scouted by simply looking for the right kind of woods. Yes, the other sign like peeled limbs, old dams and mud pies all pointed to a live stream, but knowing the look of the vegetation was key, as well.

For New England or Great Lakes trappers, it was the poplar with its paint-green leaves, while the Western beaver trapper scouts for cottonwood or aspen. To a beaver these trees are like a good feed of gourmet food, and they are willing to dig canals or travel upstream to get this juicy timber. Like a trapper who boarded 200 plews a season always told me — find the poplar and find the beaver. It’s proven time and again to be good advice.

Farm country abounds with edges in low valleys that can run for miles, and can be fur hotspots. These places allow travel under the radar and out of sight — perfect for a snare line. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout.

Another way to use terrain and vegetation is to seek out the differences in agricultural field layout. Look at the way fields are planted and you’ll see that most times they are set up at right angles. One will run south while the other will come in from the west at a 90-degree angle. Now, check the head land between both and I’ll bet there will be canine tracks and some raccoon, as well. Come harvest time these visits will increase and if there is no fall plowing, oh boy are you set for some long-term action. A couple sets at opposite ends will nail the regular travelers and if kept working, the dispersal crowd will be along soon after.

Understanding the geography, the watersheds and the vegetation of a potential trapline all can add to a successful season. Too often trappers work against the terrain instead of harnessing its conditions. Take the time to study a few maps and aerial photos, and thoroughly scout on foot. Pretty soon you`ll find plenty of potential on your trapline terrain.